Background

In the previous article, I showed some photographs of beaches in southern Rhode Island. One included chimney remains in the surf zone. These were remnants from before 1938, when the "Long Island Express" roared ashore in Long Island and devastated coastal communities throughout southern New England.

For background on the great storm, an episode of

American Experience, titled "

The Hurricane of '38" is fascinating viewing. The

transcript is also available online. Below is an excerpt from my paper in

Journal of Coastal Research. The text is long, so feel free to skim. The map below shows the tracks of some of the most destructive hurricanes to pass over New England.

|

| Most powerful New England hurricanes. Locations from NOAA. Background map from ESRI Data and Maps |

John Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay Colony and William Bradford of Plymouth described the

1635 hurricane in their diaries. NOAA recreated the approximate path with modern modeling techniques. Ludlum (1963) in

Early American Hurricanes provides more details of The Great Colonial Hurricane.

|

| Pawtuxet Village, 1938 |

|

| "General destruction in the upper harbor. Workboat floated up on land by stormsurge. New England Hurricane of 1938" |

Source:

Collection Location: Other

Photo Date: 1938 September 22

Credit: Donated by Susan Medyn, Tiverton, Rhode Island

September 1938 Hurricane

The Great New England Hurricane of September 21, 1938, was one of the seminal meteorological events in New England's 20th century history. The storm caused unprecedented damage throughout New England and Long Island, killed over 600 people, and devastated coastal communities along the open Atlantic shore, Long Island Sound, Block Island Sound, Narragansett Bay, and Buzzards Bay (Allen, 1976; Federal Writers' Project, 1938; Minsinger, 1988). On Long Island alone, the death toll was 60. The damage was beyond anything that 20th century northeast residents had ever experienced or recorded. Throughout New York and New England, the wind and water felled 275 million trees, seriously damaged more than 200,000 buildings, knocked trains off their tracks, and beached thousands of boats (Haberstroh, 1998). Wind and rain damage extended as far north as Rutland, Vermont, entire city blocks burned in New London and other industrial towns, and downtown Providence, Hartford, and other cities flooded.

Various writers estimated damage from the storm at $600 million in 1938 dollars. Pielke and Landsea (1998) estimated damage of $306 million for the affected coastal counties. They recalculated the loss to be $16.6 billion in 1995 dollars by normalizing the damage by inflation, personal property increases, and coastal county population changes. Therefore, if we double their base damage estimate to $600 million to include inland counties that experienced flooding, the normalization to 1995 dollars might be in the range of $32 billion. Based on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) inflation calculator (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014), this equates to $50 billion in 2014 dollars. In comparison, Hurricane Sandy in October, 2012, caused ≈ $18.75 billion in insured property losses, excluding flood claims covered by the Federal flood insurance program (Insurance Information Institute, 2013).

The 1938 storm was first detected as a tropical depression off the Cape Verde Islands. On September 15, east of Puerto Rico, it was upgraded to a hurricane. Florida residents began to make preparations, but by the 20th, the system curved northward towards the Carolinas. A low pressure trough moving out of the Great Lakes had enough strength to steer the hurricane away from the coast. Further out to sea, a Bermuda high was in place, with the result that the hurricane was squeezed between these two systems and accelerated north, but not out into the open Atlantic. The storm moved quickly up the Atlantic seaboard at over 80 km/hour, therefore gaining the name "Long Island Express." On that day, seas and winds were not particularly high, and New England and Long Island coastal residents had little warning that severe weather was headed their way. The wind grew gradually during the morning of the 21st, but by early afternoon, 130-160 km/hour winds crushed houses, knocked down trees, stripped paint from cars, and lifted barges and boats onto land (Scotti, 2003). The eye of the storm made landfall near Bellport, New York, sometime between 2:10 and 2:40 pm EST as a Category 3 (Figure 2; Landsea et al., 2014). Jarvinen (2006) lists the storm as a category 3.5 on the Saffir-Simpson scale. More detailed meteorological information can be found in Myers and Jordan (1956), Pierce (1939), Tannehill (1938), Vallee and Doin (1998) and Wexler (1939). Harris (1963) documented high water survey and tide data.

Hurricane force winds were felt throughout New England, and the Blue Hill Observatory in Milton, Massachusetts (10 km south of Boston) recorded a gust of 310 km/hour. By the 22nd, the storm had moved north into southern Canada and dissipated much of its energy, leaving a path of forest and coastal destruction.

Much of the inland flooding was not caused by the hurricane itself. Rainfalls of over 2.5 cm had fallen over broad areas of southern and central New England on both September 12 and 15, causing a significant rise in river levels. On September 17-20, another storm dropped more than 15 cm rainfall, sufficient to produce flooding over many tributary rivers throughout New England (NOAA, 2012). The stage was set for the hurricane on the 21st, which dropped more than 15 cm of rain. The Thames drainage in Connecticut, where over 33 cm were recorded, was particularly hard hit, resulting in some of the worst flooding ever recorded. The Connecticut River in Hartford reached a level of 7.7 m, which was 5.9 m above flood stage. The author's father worked for the USACE Providence District at this time and was assigned to stream gauging in the Connecticut valley. He wrote in his diary that many roads in Connecticut were under water, washed out, or impassible because of fallen trees and debris.

Coastal residents suffered the greatest from the storm because the surge coincided almost exactly with the autumnal high tide. Long Island and southern Rhode Island residents reported that an 8-12 m wall of water overwashed the barrier islands with virtually no warning (Minsinger, 1988). Pore and Barrientos (1976) reported high water marks of only 1.6-4.1 m (NGVD 1929) in this area. It is unclear why survivors reported such dramatically higher water levels, unless their memories were exaggerated or all evidence in the most vulnerable area was totally destroyed. One of the enduring geological effects of the Great New England Hurricane was the cutting of the barrier beach south of Shinnecock Bay, which, after jetty construction, became the present Shinnecock Inlet (Morang, 1999). Another change is that the storm surge blew Sandy Point free of Napatree Point in Westerly, Rhode Island, thereby greatly changing tidal exchange and shoal migration in Little Narragansett Bay.

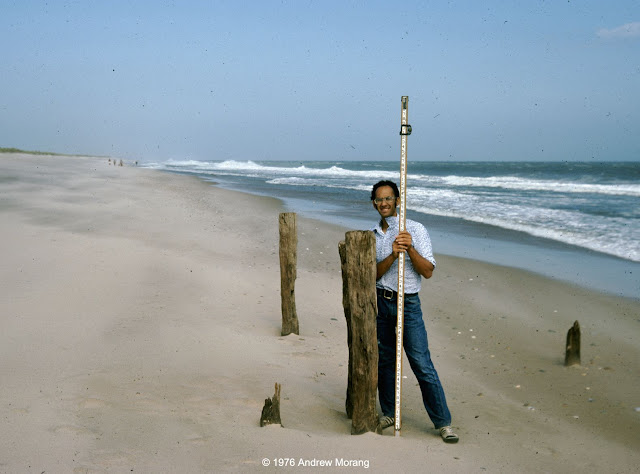

Along the southern Rhode Island shore, the storm washed away entire beach communities. This author has seen remnants of chimneys and foundations exposed in the sand on East Beach, Rhode Island, after winter storms lowered the sand elevation. The surge funneled up Narragansett Bay, causing untold damage to East Greenwich, Barrington, Warwick, and Portsmouth (Providence Journal, 1938). The business district of Providence was flooded with over 4 m of water, submerging trolley cars, automobiles, and the ground floors of buildings. The incoming water entered the city so swiftly, within 10 minutes, the downtown was engulfed, trapping people in the upper floors of buildings, and, tragically, in automobiles. It was almost two weeks before many stores and businesses could dig out debris, pump flooded basements, restore electricity, and resume business.

Viewing these events after six decades, we wonder, why were people caught so unawares by this storm? Along with the fact that the storm moved so quickly up the coast from Florida to New England, four factors may account for the tragedy.

First, Weather forecasters, without the benefit of satellites or storm-chasing aircraft, were unable to effectively track it.

Second, in that era, many forecasters discounted the possibility of a hurricane making landfall in New England, and the weather service was accused of underestimating the danger of the storm and not issuing adequate warnings (Scotti, 2003; Burns, 2005). This erroneous belief persisted despite numerous historical records of earlier major hurricanes, including ones in 1635, 1638, 1815, and 1869 (Ludlum, 1963) .

Third, Radio stations and newspapers were unable to spread warnings to all the affected areas. The afternoon newspapers had not yet been distributed by the time the storm struck Long Island in mid-afternoon.

Finally, an intriguing historical note: Burns (2005) and Clowes (1939, p. 60) stated that Long Island residents were distracted with other news. "However, reports received by the Weather Bureau indicate that owing to the general alarm over the European situation the public took little interest in news regarding the weather." On September 21, 1938, the Czech parliament capitulated to Adolf Hitler and accepted cession of the territories with a German-speaking majority, the Sudentenland. The Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Neville Chamberlain, flew to Munich to negotiate with Adolph Hitler about the partition of Czechoslovakia in the attempt to avert war (Churchill, 1948). Americans and Europeans, terrified that another world conflagration might break out, anxiously listened to wireless broadcasts from Germany hoping that Chamberlain might appease the German dictator.

References

Allen, E.S., 1976. A Wind to Shake the World. New York: Little Brown & Co., 288p.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2014. Consumer Price Index. Washington, D.C: U.S. Department of Labor. URL: http://www.bls.gov/cpi/.

Burns, C., 2005. The Great Hurricane: 1938. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 230p.

Churchill, W.S., 1948. The Second World War, the Gathering Storm. Boston, Massachusetts: Houghton Mifflin, 752p.

Clowes, E.S., 1939. The Hurricane of 1938 on Eastern Long Island. Bridgehampton, New York: Hampton Press, 67p.

Federal Writers' Project, 1938. New England Hurricane, a Factual, Pictorial Record. Written and compiled by members of the Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration in the New England States. Boston, Massachusetts: A Hale, Cushman & Flint, 220p.

Haberstroh, J., 1998. When the superstorm hit, Westhampton exhibit recalls deadly Hurricane of '38. Hempstead, New York: Newsday A3, A49 (newspaper article dated Sunday, September 20, 1998).

Harris, D.L., 1963. Characteristics of the Hurricane Storm Surge. Washington, D.C.: Weather Bureau, U.S. Department of Commerce, Technical Paper No. 48, 139p.

Insurance Information Institute, 2013. Hurricanes. URL: http://www.iii.org/facts_statistics/hurricanes.html .

Jarvinen, B., 2006. Storm Tides in Twelve Tropical Cyclones (including Four Intense New England Hurricanes). Miami, Florida: Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory, Hurricane Research Division, 99p.

Landsea, C.W., Hagen, A., Bredemeyer, W., Carrasco, C., Glenn, D.A., Santiago, A., Strahan-Sakoskie, D., and Dickinson, M. 2014. A reanalysis of the 1931 to 1943 Atlantic hurricane database. Journal of Climate 2014 ; e-View doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1175/JCLI-D-13-00503.1.

Ludlum, D.M., 1963. Early American Hurricanes, 1492-1870. Boston, Massachusetts: American Meteorological Society, 198p.

Minsinger, E.E. (ed.), 1988. The 1938 Hurricane, an Historical and Pictorial Summary. East Milton, Massachusetts: Blue Hill Observatory, 128p.

Morang, A., 1999. Coastal Inlets Research Program, Shinnecock Inlet, New York, Site Investigation, Report 1, Morphology and Historical Behavior. Vicksburg, Mississippi: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Waterways Experiment Station, Technical Report CHL-98-32, 94p. and appendices.

Myers, V. A. and Jordan, E. S., 1956. Winds and pressure over the sea in the Hurricane of September 1938. Monthly Weather Review, 84(7), 261-270.

NOAA, 2012. Historical Floods in the Northeast, Northeast River Forecast Center. URL: https://www.weather.gov/nerfc/HistoricFloods.

Pielke, R.A., Jr., and Landsea, C.W., 1998. Normalized hurricane damages in the United States: 1925-95. Weather and Forecasting, 13(3), 621:631.

Pierce, C. H., 1939. The meteorological history of the New England Hurricane of September 21, 1938. Monthly Weather Review, 67(8), 237-285.

Pore, N.A. and Barrientos, C.S., 1976. Storm Surge. MESA New York Bight Atlas Monograph Number 6. Albany, New York: New York Sea Grant Institute, 43p.

Providence Journal, 1938. The Great Hurricane and Tidal Wave ^ Rhode Island September 21, 1938. Providence, Rhode Island: Providence Journal Company, 130p.

Scotti, R.A., 2003. Sudden Sea: The Great Hurricane of 1938. Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, 277p.

Tannehill, I.R., 1938. Hurricane of September 16 to 22, 1938. Monthly Weather Review, 66(9), 286-288.

Vallee, D.R. and Dion, M.R., 1998. Southern New England Tropical Storms and Hurricanes, A Ninety-eight Year Summary 1909-1997. Taunton, Massachusetts: National Weather Service.

Wexler, R., 1939. The filling of the New England Hurricane of September 1938. Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society, 20(7), 277-281.

Appendix A. Additional Bibliography of the Great New England Hurricane of 1938 (Printed documents)

Bennett, H. H. 1939. A permanent loss to New England: Soil erosion resulting from the hurricane. Geographical Review Vol. 29, 196-204.

Bennett, J. P. (ed.). 1998. The 1938 hurricane as we remember it, Volume II, A collection of memories from Westhampton Beach and Quogue Areas. Quogue Historical Society, Quogue, NY, and Westhampton Beach Historical Society, Westhampton Beach, NY (Searles Graphics, Inc., East Patchogue, NY).

Brickner, R. K. 1988. The Long Island Express, Tracking the Hurricane of 1938. Hodgins Printing Co., Batavia, NY (with historical data by David M. Ludlum).

Brooks, C. F. 1939. Hurricanes into New England: Meteorology of the storm of September 21, 1938. Geographical Review Vol. 29, pp 119-127.

Cummings, M. 2006. Hurricane in the Hamptons, 1938. Arcadia Publishing, 128 p.

Francis, A. A., 1998: Remembering the Great New England Hurricane of 1938. The Salem Evening News, pp. unknown.

Goudsouzian, A. 2004. The Hurricane Of 1938 (New England Remembers). Commonwealth Editions, 90 p.

Hendrickson, R. G. 1996. Winds of the fish’s tail. Amereon Ltd., Mattituck, NY.

Perry, M. B., and Shuttleworth, P. D., (ed.). 1988. The 1938 Hurricane as We Remember it, a Collection of Memories from Westhampton Beach and Quogue. Quogue Historical Society, Quogue, NY (Prepared by the Quogue Historical Society on the fiftieth anniversary of the 1938 hurricane).

Shaw, O. 1939. History of the storms and gales on Long Island; and Quick, D., The Hurricane of 1938. Long Island Forum, Bay Shore, NY (limited edition of 500 copies).

Vallee, D.R., 1993. Rhode Island Hurricanes and Tropical Storms, A Fifty-Six Year Summary 1936-1991. NOAA Technical Memorandum NWS-ER-86, Bohemia, NY, 62 pp.

Wood, F. J. 1976. The Strategic Role of Perigean Spring Tides in Nautical History and North American Coastal Flooding, 1635-1976. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

Note: More papers and books may exist.