Long-term readers may remember my

2010 article on the group of condemned beach houses at South Nags Head, North Carolina. In 2010, the surf zone was literally under the piles that supported the houses, and everyone assumed they would soon collapse. The City had condemned them because of exposed septic tanks.

To everyone's surprise, the houses are still standing. And now they are perched on a beautiful wide beach, courtesy of the recently-completed beach fill. I do not understand all the details, but the owners are suing the city to be allowed to re-access their properties so that they can fix them up and un-condemn them. Only in America....

The beach nourishment project was conducted between May 24 and October 27 of 2011. Hurricane Irene on August 27 interrupted the work. For safety, the dredging company moved their equipment to Norfolk, Virginia. Storm waves caused extensive adjustment of the nourished beach profile, but no loss of sand within the project area (Kana

et al., 2012).

Adjustment means sand moved deeper on the profile and morphologic features like sand bars formed, but the overall volume of sand remained within the project boundaries. Because of delays in securing federal funds for a comprehensive Dare County beach nourishment project, the Town of Nags Head elected to fund an "interim" beach nourishment locally. Total sand placement amounted to 4,600,000 cubic yards. This may be the largest locally-funded beach nourishment project completed in the United States.

Some notes on beach projects:

Some notes on beach projects:

When confronted with severe beach erosion, local, county, and Federal authorities can choose four broad classes of technical and management alternatives (

Coastal Engineering Manual, 2008, Part V.3):

- No action

- Controlled and strategic retreat

- Hold the line and refuse to retreat

- Replicate or augment the natural sediment supply to the region with artificial beach nourishment.

1. The first option is often followed on undeveloped coasts, such as in National Seashores. But even the National Park Service is now selecting to add sand to some of their eroding parks.

2. The second option, strategic retreat, is politically difficult because property owners lobby their politicians to "do something" to protect their valuable beach-front property. And, towns and municipalities derive major tax revenue from beach property, whose owners are often wealthy and often only occupy the premises temporarily.

Nevertheless, in the face of rising sea level, many communities are confronting the previously unthinkable fact that some areas will be impossible to protect and maintain. Also, taxpayers from inland areas complain that wealthy beach residents voluntarily purchased their properties in hazardous geographic locations. Why should general taxpayer revenues pay for storm recovery to let wealthy people live at the beach and profit from the appreciation of their houses (

i.e., capitalism for the profit, but socialize the risk)?

3. The third option, "hold the line," was popular in the early-mid 20th century. It consists of building massive sea walls or shore-front stone revetments to mark the permanent position of the shoreline. One side is ocean, the other is city. The 1900-vintage Galveston Seawall is an example of this type of project. Seawalls have many disadvantages. They:

- Are difficult to design and expensive to construct.

- Have aesthetic issues

- Require maintenance and are vulnerable to major storms.

- Are environmentally troublesome (there is little habitat in front of a concrete wall).

- Offer only limited recreational opportunities.

Because of cost, environmental, and permitting issues, we will probably not see new major seawall construction in the United States.

4. The fourth option is more and more popular around the world. A beach nourishment project has as its intent to replace sand onto a shoreface from where sand was lost over the years due to natural and man-made reasons. Most beaches around the United States are far from "natural" any more, and most are sediment-deficient because of various man-made reasons. These include:

- Dam-construction on rivers

- Sediment trapping by jetties at inlets

- Sand lost offshore due to harbor and channel dredging, followed by deep-water disposal.

- Sand-mining from beaches

- Loss of sand sources due to paving and urbanization

- Armoring of bluffs and banks

The concept of a beach fill is to pump sand onto the beach from an offshore deposit or bring in sand using trucks. The South Nags Head project is an example of hydraulic pumping from an offshore deposit.

Many critics state that a beach fill is fundamentally a failure because eventually the sand will wash away. Of course it will - that is the function of a beach! The beach serves as a flexible and sacrificial buffer to dissipate storm wave energy and protect upland development. Regular maintenance is one of the costs of living at the beach. The cost of periodic renourishment is low compared to the economic activity generated by wide recreation beaches. Think of the alternative: who comes to the coast to look at a seawall?

This is a view of the barrier island at Duck, about 25 miles north of South Nags Head. Unlike Nags Head, Duck has been relatively stable and has not suffered net beach erosion over the last half century. In this view, the Atlantic ocean is to the left and Currituck Sound to the right. The undeveloped land in the foreground belongs to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and is used for their Field Research Facility. It was originally a bombing range in World War II and reverted to the Corps of Engineers in the late 1960s. It is obvious where commercial property begins beyond the Army property. Much of the island has been so thickly developed, it is essentially urban.

On the Federal land, the first row of sand dunes is thickly vegetated. The frontal dune all along the Outer Banks was built by the Civilian Conservation Corps during the 1930s - another example that the beaches are not "natural." This is a photograph from the 43-m (120 ft) observation tower, which is used for experiments and continuous video imaging.

This is a view of the research pier. Long-period swells are approaching almost perpendicular to the shore. This is the best view in Duck other than from an airplane!

The view north from the tower shows some palatial vacation "bungalows."

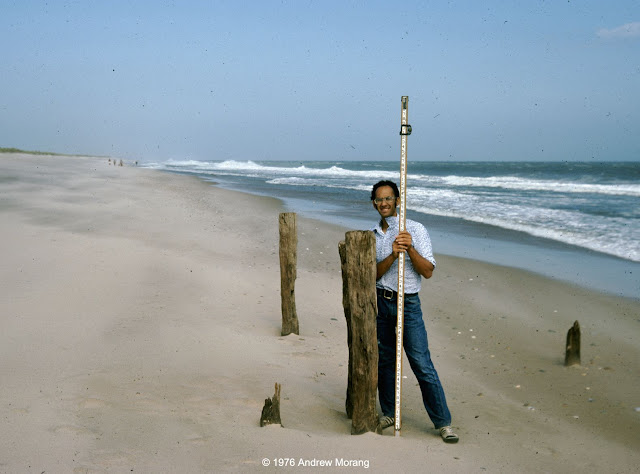

This photograph shows workers planting grass on a beach restoration project. The date and location were not recorded, but the scene is likely the Outer Banks. The National Park Service and other Federal agencies sponsored many dune and beach restoration during the late 1930s. These also served as work relief efforts during the Great Depression. Photograph from the Beach Erosion Board Archives, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (from the

Coastal Engineering Manual, Part I, Chapter 3). For more information on dune construction, see Schroeder, Dolan, and Haden (1976).

References:

Coastal Engineering Manual. 2008. Shore Protection Projects, Part V, Chapter 3. Engineer Manual EM-1110-2-1100, US Army Corps of Engineers, Washington, DC (avail. online, http://publications.usace.army.mil/publications/eng-manuals/EM_1110-2-1100_vol/PartV/Part_V-Chap_3.pdf, accessed 22 June 2012).

Kana, T.W., Kaczkowski, H.L., Traynum, S.B., and McKee, P.A. 2012. Impact of Hurricane Irene during the Nags Head Beach Nourishment Project. Shore & Beach, Vol. 80, No. 2, pp. 6-18.

Schroeder, P.M., Dolan, R., and Hayden, B.P. 1976. Barrier-dune construction on the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Environmental Management, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 105-114.