|

| Ankor temples from tourismcambodia.com |

Introduction

One of the most total and overwhelming examples of the collapse and disappearance of a civilization is the Khmer Empire (Khmer: ចក្រភពខ្មែរ) or the Angkor Empire (Khmer: ចក្រភពអង្គរ), whose remains are in present-day Cambodia. The empire thrived from the 9th - 15th centuries, during which the emperors developed a society of immense wealth and sophistication. At its peak, the capital, Angkor, covered 1000 square miles. The empire depended on a highly sophisticated water supply system consisting of reservoirs and canals. The reservoirs stored water during the monsoon and distributed it in the dry season. Some evidence shows that the large ponds surrounding the palaces had fish aquaculture. The city state grew in population until it exceeded 1 million, far exceeding any European city at the time.

|

| Moat at Ankor Wat. Was this once used for fish aquaculture? Note the perfect linear steps. |

As written in Wikipedia,

"Its greatest legacy is Angkor, in present-day Cambodia, which was the site of the capital city during the empire's zenith. The majestic monuments of Angkor — such as Angkor Wat and Bayon — bear testimony to the Khmer empire's immense power and wealth, impressive art and culture, architectural technique and aesthetics achievements, as well as the variety of belief systems that it patronised over time. Recently satellite imaging has revealed Angkor to be the largest pre-industrial urban center in the world."What caused the collapse? Common hypotheses include:

- Warfare (as an example, the destruction the Inca and Aztecs)

- Environmental degradation and collapse (Easter Island)

- Political decay and inability to maintain the colossal infrastructure

- Disease or a pandemic

- Demographic changes (i.e., low birthrates or mass migration)

- Political paralysis

- Massive crumbling infrastructure

- Money squandered on foreign wars and transfer payments

- Corruption in the highest offices of the government as well as local governments

- Looming water shortages in areas that are over-populated considering their natural resources (i.e., much of the US West)

- A portion of the population in open revolt against the central government

The incredible complex of temples, ruins, and giant smothering trees at Ankor is one of the world's great photographic topics. The stones, rocks, carved faces, and encroaching jungle are endlessly fascinating. Lara Croft: Tomb Raider and Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom include scenes filmed here.

Temple of Ta Prohm

|

| Local man climbing spire at Ta Prohm |

|

| Stone columns, Ta Prohm |

"In 1186 A.D., Jayavarman VII embarked on a massive program of construction and public works. Rajavihara ("monastery of the king"), today known as Ta Prohm ("ancestor Brahma"), was one of the first temples founded pursuant to that program. The stele commemorating the foundation gives a date of 1186 A.D."

"The trees growing out of the ruins are perhaps the most distinctive feature of Ta Prohm, and "have prompted more writers to descriptive excess than any other feature of Angkor." Two species predominate, but sources disagree on their identification: the larger is either the silk-cotton tree (Ceiba pentandra) or thitpok Tetrameles nudiflora, and the smaller is either the strangler fig (Ficus gibbosa) or gold apple (Diospyros decandra). Angkor scholar Maurice Glaize observed, "On every side, in fantastic over-scale, the trunks of the silk-cotton trees soar skywards under a shadowy green canopy, their long spreading skirts trailing the ground and their endless roots coiling more like reptiles than plants."

Temple of Banteay Srei

|

| Detail of carved sandstone, Banteay Srei |

|

| Door ornamentation at Banteay Srei. Note the sophisticated figurine carving. |

"Banteay Srei or Banteay Srey (Khmer: ប្រាសាទបន្ទាយស្រី) is a 10th-century Cambodian temple dedicated to the Hindu god Shiva. Located in the area of Angkor, it lies near the hill of Phnom Dei, 25 km (16 mi) north-east of the main group of temples that once belonged to the medieval capitals of Yasodharapura and Angkor Thom. Banteay Srei is built largely of red sandstone, a medium that lends itself to the elaborate decorative wall carvings which are still observable today. The buildings themselves are miniature in scale, unusually so when measured by the standards of Angkorian construction. These factors have made the temple extremely popular with tourists, and have led to its being widely praised as a "precious gem", or the "jewel of Khmer art."

|

| Monumental entry hall, Banteay Srei |

|

| Guardian lions, entry hall, Banteai Srei. Do these look Egyptian to you? |

Just imagine the monumental cost of mining, transporting, carving, and erecting all this stone. And look at the astonishing quality of the rock carving. Did the workers have early-technology steel tools for this work? How did the Khmer emperors/kings afford these projects?

To be continued.....

Appendix - Background information from BBC

Beyond Angkor: How lasers revealed a lost city

By Ben Lawrie

Documentary film-maker

- Published

Deep in the Cambodian jungle lie the remains of a vast medieval city, which was hidden for centuries. New archaeological techniques are now revealing its secrets - including an elaborate network of temples and boulevards, and sophisticated engineering.

In April 1858 a young French explorer, Henri Mouhot, sailed from London to south-east Asia. For the next three years he travelled widely, discovering exotic jungle insects that still bear his name.

Today he would be all but forgotten were it not for his journal, published in 1863, two years after he died of fever in Laos, aged just 35.

Mouhot's account captured the public imagination, but not because of the beetles and spiders he found.

Readers were gripped by his vivid descriptions of vast temples consumed by the jungle: Mouhot introduced the world to the lost medieval city of Angkor in Cambodia and its romantic, awe-inspiring splendour.

"One of these temples, a rival to that of Solomon, and erected by some ancient Michelangelo, might take an honourable place beside our most beautiful buildings. It is grander than anything left to us by Greece or Rome," he wrote.

His descriptions firmly established in popular culture the beguiling fantasy of swashbuckling explorers finding forgotten temples.

Today Cambodia is famous for these buildings. The largest, Angkor Wat, constructed around 1150, remains the biggest religious complex on Earth, covering an area four times larger than Vatican City.

It attracts two million tourists a year and takes pride of place on Cambodia's flag.

But back in the 1860s Angkor Wat was virtually unheard of beyond local monks and villagers. The notion that this great temple was once surrounded by a city of nearly a million people was entirely unknown.

It took over a century of gruelling archaeological fieldwork to fill in the map. The lost city of Angkor slowly began to reappear, street by street. But even then significant blanks remained.

Then, last year, archaeologists announced a series of new discoveries - about Angkor, and an even older city hidden deep in the jungle beyond.

An international team, led by the University of Sydney's Dr Damian Evans, had mapped 370 sq km around Angkor in unprecedented detail - no mean feat given the density of the jungle and the prevalence of landmines from Cambodia's civil war. Yet the entire survey took less than two weeks.

Their secret?

Lidar - a sophisticated remote sensing technology that is revolutionising archaeology, especially in the tropics.

Mounted on a helicopter criss-crossing the countryside, the team's lidar device fired a million laser beams every four seconds through the jungle canopy, recording minute variations in ground surface topography.

The findings were staggering.

The archaeologists found undocumented cityscapes etched on to the forest floor, with temples, highways and elaborate waterways spreading across the landscape.

"You have this kind of sudden eureka moment where you bring the data up on screen the first time and there it is - this ancient city very clearly in front of you," says Dr Evans.

These new discoveries have profoundly transformed our understanding of Angkor, the greatest medieval city on Earth.

At its peak, in the late 12th Century, Angkor was a bustling metropolis covering 1,000 sq km. (It would be another 700 years before London reached a similar size.)

Angkor was once the capital of the mighty Khmer empire which, ruled by warrior kings, dominated the region for centuries - covering all of present-day Cambodia and much of Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Myanmar. But its origins and birthplace have long been shrouded in mystery.

A few meagre inscriptions suggested the empire was founded in the early 9th Century by a great king, Jayavarman II, and that his original capital, Mahendraparvata, was somewhere in the Kulen hills, a forested plateau north-east of the site on which Angkor would later be built.

But no-one knew for sure - until the lidar team arrived.

The lidar survey of the hills revealed ghostly outlines on the forest floor of unknown temples and an elaborate and utterly unexpected grid of ceremonial boulevards, dykes and man-made ponds - a lost city, found.

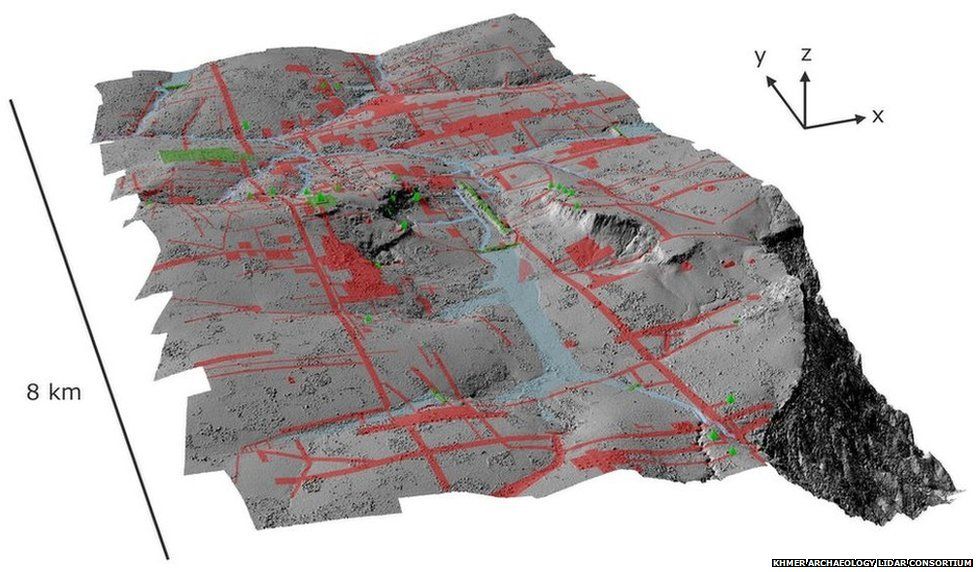

Lidar technology has revealed the original city of Angkor - red lines indicate modern features including roads and canals. Image copyright Khmer Archaeology LiDAR Consortium

Lidar technology has revealed the original city of Angkor - red lines indicate modern features including roads and canals. Image copyright Khmer Archaeology LiDAR ConsortiumMost striking of all was evidence of large-scale hydraulic engineering, the defining signature of the Khmer empire.

By the time the royal capital moved south to Angkor around the end of the 9th Century, Khmer engineers were storing and distributing vast quantities of precious seasonal monsoon water using a complex network of huge canals and reservoirs.

Harnessing the monsoon provided food security - and made the ruling elite fantastically rich. For the next three centuries they channelled their wealth into the greatest concentration of temples on Earth.

One temple, Preah Khan, constructed in 1191, contained 60t of gold. Its value today would be about £2bn ($3.3bn).

But despite the city's immense wealth, trouble was brewing.

At the same time that Angkor's temple-building programme peaked, its vital hydraulic network was falling into disrepair - at the worst possible moment.

The end of the medieval period saw dramatic shifts in climate across south-east Asia.

Tree ring samples record sudden fluctuations between extreme dry and wet conditions - and the lidar map reveals catastrophic flood damage to the city's vital water network.

With this lifeline in tatters, Angkor entered a spiral of decline from which it never recovered.

In the 15th Century, the Khmer kings abandoned their city and moved to the coast. They built a new city, Phnom Penh, the present-day capital of Cambodia.

Life in Angkor slowly ebbed away.

When Mouhot arrived he found only the great stone temples, many of them in a perilous state of disrepair.

Nearly everything else - from common houses to royal palaces, all of which were constructed of wood - had rotted away.

The vast metropolis that once surrounded the temples had been all but devoured by the jungle.